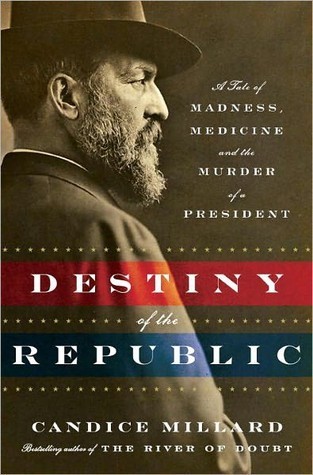

Book Review Destiny of the Republic

Millard, Candice. Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President. New York: Doubleday, 2011.

Four American Presidents have been assassinated over the course of our nation’s history. The assassinations of Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy are well known to most Americans and the images of those tragic events are familiar to all. The assassination of William McKinley would propel Theodore Roosevelt to the White House, leading to a period of great expansion as the United States became a world power. But what of James A. Garfield? The 20th President has become largely just a name to most. A little known in a long line of forgettable names to occupy the office during the last half of the 19th Century. Canice Millard’s book: Destiny of the Republic brings a remarkable story to life.

Born near Cleveland, Ohio, on November 19, 1831, Garfield was the last of the “log cabin” Presidents. His father Abram, a farmer who had cleared the family homestead in Cuyahoga County, died when James, his youngest, was not yet two. His mother Eliza insisted that he work hard and learn by reading anything he could. Life on a farm and their poor existence did not deter Eliza Garfield from wanting an education for her four children, but first James would work to help the family, including a short time as a driver on the Erie and Ohio Canal.

Using just $17 his mother could scrape together, Garfield enrolled at Williams College at the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, now Hiram College in Hiram. Ohio. A part-time janitor and student, Garfield was teaching in his second semester and was soon the president of the college by age 26. It was at Williams College that Garfield met Lucretia Rudolph, and the romance that would last for the rest of their lives began. They married in 1858.

During the Civil War, Garfield was commissioned Lieutenant Colonel of the 42nd Ohio regiment and quickly became its Colonel. He rose to command a brigade and soon found himself a General and Chief of Staff to General William S. Rosecrans. 1863, Garfield left the army to become a candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives. A Republican, he won, and his 17-year career in politics began.

It was, however, at the 1880 Republican National Convention in Chicago that Garfield would find himself the nominee of his divided party-not something he had planned on. The delegates could not agree on a candidate, former President U.S. Grant, James G. Blaine and John Sherman were all vying for the nomination, but there was no clear frontrunner. Suddenly, one delegate put forward Garfield’s name. To his surprise, the delegates began to fall in behind him and on the 36th ballot, James A. Garfield was nominated as the Republican candidate for President.

Campaigning from his home in Mentor, Ohio, Garfield would defeat the Democratic nominee and fellow former Civil War general Winfield S. Hancock of Pennsylvania with one of the narrowest margins in American history that November.

Though his Presidency was cut short on July 2, 1881 by an assassin’s bullet, Garfield had managed to stand up to the presumed head of the Republican Party, Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York and his own Vice-President and Conkling ally Chester A. Arthur. He had begun to push ahead legislative issues of his own.

Throughout her book, Millard takes the reader behind the scenes of Garfield’s relationship with his wife and their five children while telling the story of the United States of the late 19th Century, a time of westward expansion, economic growth and scientific innovations. It should have been a shining time for the county had it not been for the madness of Charles Guiteau.

Guiteau was a failure in everything he had tried in life-suffering from syphilis, a failed law career, even failing at a free-love colony where the women called him “Charles Gitout.” Early in Garfield’s Presidency, Guiteau sought an appointment as U.S. Minister to France. He had visited Secretary of State James G. Blaine and written countless letters promoting himself as the right man for the post. Blaine ignored or denied all Guiteau’s appeals. Guiteau was a frequent visitor to the White House and sent dozens of letters to the President concerning his appointment. Garfield’s aides soon became tired of the disheveled and irksome man’s presence and his letters. Guiteau became obsessed with Garfield, his last hope.

Guiteau began to stalk the President during the spring of 1881. He bought a .44 caliber revolver and soon determined assassination was his last hope; perhaps Chester Arthur would be more favorably inclined to appoint him he thought. On July 2, 1881, Guiteau shot Garfield once in the arm, an insignificant wound, and once in the back, as the President and Secretary Blaine walked through the Baltimore and Ohio train station in Washington, D.C. Guiteau was quickly overpowered and arrested.

Doctors soon arrived on the scene and, as was common practice of the day, probed the wound with unsterilized fingers and probes. Soon Garfield was moved to the stifling White House where Dr. D. Willard Bliss took charge. Bliss continued to probe the wound in the back, administer enemas of alcohol, egg yolk and broth. Bliss administered mercury laden medicines, all of which made the President violently ill and malnourished. Bliss continued to probe with unsterilized probes, looking for the bullet.

It is here Millard weaves in the story of Dr. Joseph Lister and his theories of sterilization, not yet popular in the U.S., and the young inventor Alexander Graham Bell, whose crude metal detector was utilized to locate the bullet somewhere inside Garfield. Bliss, a surgeon during the Civil War, did not believe in sterilization and only reluctantly allowed Bell to search for the bullet. As the summer wore on, a revolutionary air conditioning system was installed in the room where Garfield lay to ease his suffering. Nothing worked. Other doctors’ advice was ignored or not permitted, even when Lucretia Garfield begged her husband to seek another opinion.

Obsessed with the sea since boyhood, Garfield was taken by special train to the cottage on the Jersey Shore where he had been headed all along. He died there on September 19, 1881. He was 49.

At the autopsy, doctors were shocked. Garfield’s body was filled with infection. The bullet was on the wrong side of his body from were Bliss had insisted it was. The bullet had hit no vital organs. Dr. Bliss had killed him. He had finished the assassin’s job. Charles Guiteau was convicted of murder and hanged on June 30, 1882.

Millard’s book is filled with fascinating details about the participants, from Garfield and Guiteau to Dr. Bliss, Bell and Lister. The political intrigues of Conkling and Arthur make fascinating reading. Destiny of the Republic is a must read for anyone interested in American history and the late 19th Century. The writing style is fast paced, but not hurried, reading like a novel.

What could James A. Garfield have accomplished? How would he be known today, but for the act of a madman.

For those interested in a short day trip, Garfield’s home “Lawnfield” in Mentor, Ohio, restored and administered by the National Park Service is open to the public. Nearby in Cleveland, Garfield’s Monument can be found in Lake View Cemetery. The caskets of James and Lucretia Garfield are entombed there.