On a beautiful September Friday in 1813, Oliver Hazard Perry’s nine-ship squadron of hastily built ships and converted merchant vessels defeated a six-ship British squadron off Put-in-Bay at the western end of Lake Erie. It was the first time in United States naval history that an entire enemy fleet was captured. This meant American control of the lake.

The story of Perry’s victory began the previous year. The United States declared war on Britain in the summer of 1812. Tensions had been brewing for some time. Westward expansion of the fast-growing nation was stalled by native tribes of the Midwest and stirred by the British in Canada and by the impressment, basically kidnapping of American sailors on the high seas, all of which fanned the flames. The United States had attempted to remain neutral, trading with both Britain and France, then embroiled in the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. In June 1812, Congress declared war on Britain.

In August 1812, Ft. Detroit, Mackinac and Ft. Dearborn (Chicago) all fell, resulting in British control of the Michigan Territory. Erie ship captain Daniel Dobbins was at Detroit when it fell and managed to make his way to Erie where Pennsylvania Militia commander for the region Gen. David Mead told him he needed to take the news of the defeat to President James Madison in Washington, D.C. There, Dobbins convinced officials of the need to build a naval squadron on Lake Erie, and he knew just the place to do it. Erie, with it’s protected bay would make a perfect place to build and equip a fleet. With $2,000 in his pocket, Dobbins returned to Erie to begin his enormous task.

The only resource at his disposal there was timber. Everything else, iron, cannon and men would have to come from elsewhere. In a hastily constructed shipyard at the foot of modern Cascade St., Dobbins began the construction or conversion of six ships in Erie. In January 1813, Commodore Isaac Chauncey, commander of all U.S. naval forces on the Great Lakes, arrived from Lake Ontario. He instructed Dobbins to enlarge two of the partially build ships. Later that winter, seasoned ship builder Noah Brown arrived and the construction of two lager brigs, later to be Named Lawrence and Niagara, began. Brown wrote “Plain work is all that is required; they will be wanted for only one battle.”

In March 1813, 27-year-old Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry arrived in Erie to take command. A veteran naval officer, Perry had been languishing without a command, most of the U.S. Navy then being blockaded in Atlantic ports by the British navy, the largest in the world. Perry faced many challenges, foremost of which was a shortage of men. Perry grew frustrated with what seemed to be a lack of cooperation with Commodore Chauncey. His fleet would set sail that August with fewer men than Perry wanted and only about 200 experienced sailors among them, and an undetermined number of African American sailors. Many of these men had seen previous service abord the U.S.S. Constitution earlier in the war. Perry complained that too many of his men were “a motley set-Negroes, soldiers and boys.” Chauncey wrote to Perry that he considered these black sailors were “amongst my best men” and they would serve gallantly during the upcoming battle. The comment by Perry was a result of frustration with recruitment not racism, and he had nothing but praise for the African American sailors.

As the American fleet neared completion, Perry drilled his men in gunnery and ship handling. The two largest American ships, Lawrence, named for naval hero Captain James Lawrence killed earlier in the war, and Niagara were both armed with 18 332 pounder carronades-short-barreled guns that were deadly at close range and 2 12 pounder long guns with a much greater range. Lt. Jesse D. Elliot would command Niagara while Perry made Lawrence his flagship. Meanwhile, the British fleet out of Amherstburg, Ontario, at the western end of the lake, was also making ready for battle. Its commander Robert Barclay had similar problems to those of Perry. Short of men and supplies, Barclay sailed his nine ships to Long Point, and established it as his headquarters. Barclay effectively blockaded Perry’s squadron inside Presque Isle Bay and should have attacked but instead withdrew toward the western end of the lake on July 31, 1813. What became know as “Perry’s Luck” was on display.

In early August, Perry’s ships sailed into the open lake. The two brigs, Lawrence and Niagara were too large to get across the sandbar at the mouth of the bay. Noah Brown ordered “camels,” large wooden barges filled with water attached to the sides of the brigs. When pumped out, the ships were lifted high enough to pass over the sandbar on refitted with the rigging and other weight that had made passage impossible. Perry’s fleet set sail for the western end of Lake Erie, in search or Barclay.

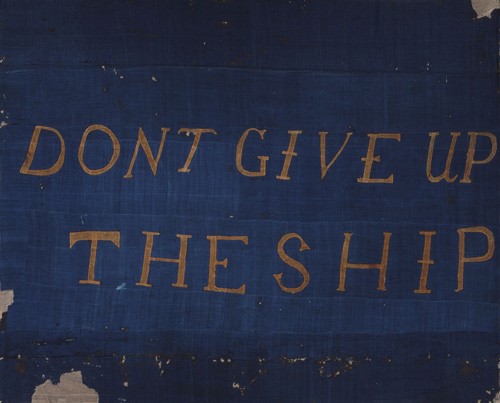

At dawn on September 10, 1813, Barclay’s fleet was sighted at anchor just to the northwest of Put-in-Bay. Perry ordered his ships “cleared for action,” the decks sprinkled with sand for traction when the blood began to flow. He ordered his new battle flag, emblazoned with the dying words of Capt. James Lawrence “Don’t Give Up The Ship.” The flag had been sewn by a group of women in Erie just for this moment.

One man was missing. Daniel Dobbins who had made it all happen was not there. Commanding officer of Ohio was sent back to Erie for supplies. Missing the battle was one of Dobbins’ greatest regrets of his life.

With the wind in his favor, Perry closed with the British who opened a tremendous hail of iron against Lawrence. 83 of her crew 0f 102 were killed or wounded as the ship was torn by the fire from the British. The deck ran red with blood. Below deck in the officer’s wardroom, assistant surgeon Usher Parsons tended to the growing number of wounded. A British shot pierced the ship’s side and tore a wounded man from his arms. Perry’s black spaniel howled through the battlef rom a storage closet below deck. Where was Niagara and Elliott?

Frustrated by the failure of Niagara to join the fight, Perry transferred his battle flag to the other brig in one of the ship’s longboats. Once aboard the Niagara (an embarrassed Elliott left in the boat Perry had come in and worked to bring up the lagging smaller ships of the fleet.) Perry brought Niagara into the battle, “Crossing the T” sailing through the now disrupted British line. Warships of the day mounted no guns fore or aft so they were defenseless. With Captain Barclay mortally wounded aboard his flagship Detroit, the British ship began to “strike their colors,” meaning lowering their flags, as sign of surrender. Perry had won the Battle of Lake Erie,

Oliver Hazard Perry would be hailed as a national hero, and the United States, like Perry, was lucky in the remaining War of 1812. Perry and Elliott would feud in writing for years to come. Perry tried to compliment Elliott, but Elliot would not let the matter rest, even after Perry’s untimely death of yellow fever on hist birthday, August 23, 1819, at the age of 34. He is buried in Newport, Rhode Island.

Today, visitors can see a bust of Perry and Perry’s sword and telescope he used in the battle at the Hagen History Center in Erie, Pennsylvania, and can visit the Erie Maritime Museum to see the reconstructed Niagara.